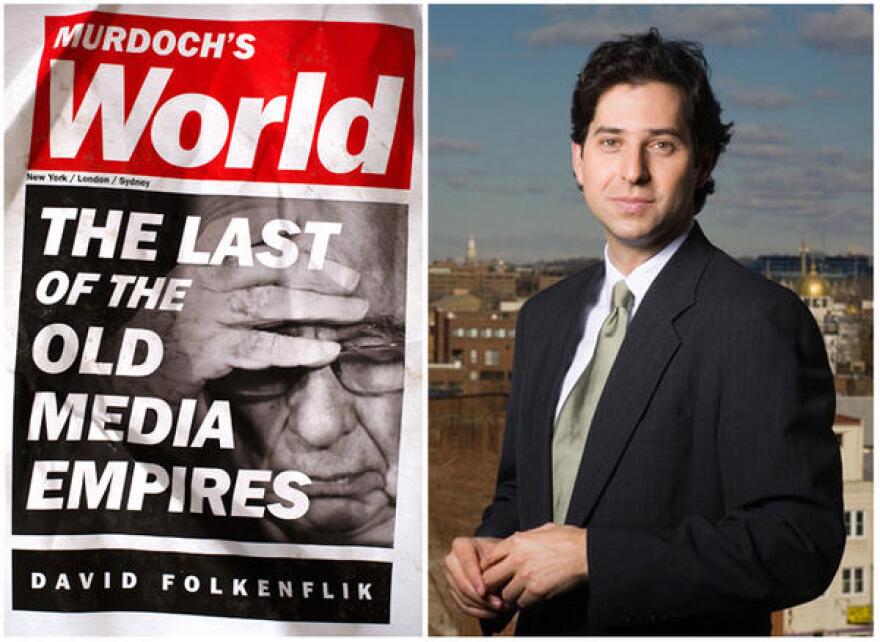

NPR media correspondent David Folkenflik has just published Murdoch’s World: The Last of the Old Media Empires, a volume that examines media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s reach across three continents—touching on Australia, North America and Europe, with a brief—and late—visit to Asia.

The book covers many issues, including Murdoch’s youth in Australia, his expansion into television and his seeming inability to penetrate the Chinese media market.

Read an excerpt from Folkenflik's book here.

Folkenflik says that Murdoch is a hardscrabble businessman who is relentless and tireless in his pursuits of new markets. And he suggests that, in some ways, Murdoch is a man of a different time, more attuned to the political and business sensibilities of the first quarter of the last century rather than the first quarter of this one.

“You could argue that Rupert Murdoch is a bit more like the William Randolph Hursts of a century ago,” Folkenflik says. “Where you have guys in just in hard-fought competition, several newspapers in the same city, in cities across the U.S. People who are interested in gossip, crime, treating politicians as sport at times."

Some say that Murdoch idealizes his friends and casts his detractors as villains, while wielding enough influence that almost no one can be indifferent to him. And so what are his values and where does one find them? Folkenflik suggests that Murdoch’s black and white ideals often show up in the most likely of places.

“They’re most clearly defined and findable in his tabloids," he says. "He loves them because of their brawling, kind of populist center-right sensibility. He switches support back and forth between two major parties in each of these three countries, politicians in both parties pay very close attention to him and are convinced that his support is necessary for their election. Even if it’s not always clear that it is necessary, they feel that they owe him something. That debt sometimes comes down to very fine, subjective interpretations of regulatory rules that are in his way.”

Folkenflik says that Murdoch is willing to court political leaders in order to expand his empire. In China, his satellite television company blocked broadcast of a BBC program on Chairman Mao that had upset Chinese officials. He also blocked the publication of a book by the last Governor General of Hong Kong just after Hong Kong reverted to Chinese rule in an attempt to gain favor with the government.

But these attempts to appease China, Folkenflik says, haven’t always worked in Murdoch’s favor.

“The Chinese authorities didn’t bend to his authority, although he kind of tried to show deference to theirs, ultimately not cracking that market as he had hoped," he says. "But, at a certain point, he gave up those desires and, I think, the Wall Street Journal has been consistent and relentless—despite trying to have a Wall Street Journal China portal that the Chinese authorities frequently block there—his reporters have consistently done very strong stories about corruption among Chinese elites.”

Murdoch, who began building his media empire in his native Australia, is also the man behind Fox News in the United States and News of the World in Great Britain. His involvement in a phone hacking scandal in Great Britain during the last decade saw some question his standards and ethics. And although that might have destroyed other men, Murdoch seemed to find a new kind of resolve.

Folkenflik says that in many ways Murdoch is the kind of person the public loves to hate.

“There are a lot things about Rupert Murdoch one should admire, whatever one’s politics are," he says. "And yet there are a lot of ways in which he introduced not only a more conservative take on the news but a crueler version of it, where people were the fodder, where people were the meat, in a sense, that were chewed up and used, whether or not they were in the public eye; whether or not they had any sophistication in dealing with the press. And then got kind of spat out. I think that’s part of his legacy, too.”

Folkenflik is hopeful that his book will bring about several discussions, including those about ethics in media and especially about whether news sources should announce themselves as partisan. There is a long tradition of print outlets announcing their politics with resolve but broadcast outlets have traditionally been more cautious. The question of how we should proceed from here, he says, is not one that is easily answered.

He recently interviewed Bill Keller, the former executive editor of the New York Times and Glen Greenwald who has of late been of The Guardian, which has been covering revelations about the NSA and surveillance.

“They take very different points of view about whether one should be impartial—and that is not carrying any belief or any particular ideology or point of view—or whether it’s better to be adversarial to government and to power and to be, almost, in a sense, hostile," says Folkenflik. "Bill Keller says, ‘You need a certain form of humility.’ Glen Greenwald says, ‘You need a certain form of antagonism to be able to ask the impertinent questions.’ They just approach it very differently."

Folkenflik says in the past half century, in major cities around the country, there weren’t a lot of newspapers and therefore they all trended toward the middle and said, "Well, we want, as best we can, to make our news coverage more in the center, so that we’ll appeal to the broadest number of readers."

Folkenflik says it’s reasonable for all readers, viewers and listeners to ask questions about how they receive their news and how that impacts the way in which they see the world.