Editor’s note: Kansas privatized its foster care system in 1997 after a lawsuit revealed widespread problems. Twenty years later, the number of Kansas children in foster care has shot up — by a third in just the last five years — and lawmakers are debating whether the system once again needs serious changes. The Kansas News Service investigated problems in the system and possible solutions. This is the first story in a series.

The Fritz family easily could have been another statistic: one more family broken by trauma and substance abuse, and two more children in a crowded Kansas foster care system.

Instead, three years later, Tara and David Fritz’s younger son shows off and shares orange Tic Tacs, which he calls “sour jelly beans,” with a visitor to their Kansas City home while waiting for his older brother to get back from school.

It was the kind of day Tara wanted to be normal for her children — unburdened by adult problems. Her own childhood wasn’t sheltered. Her father, who had a serious mental illness, died young; her mother relinquished custody of her to the state, and some of her foster parents abused her.

But after Tara and David’s second son was born, postpartum depression combined with her childhood trauma, and some days she couldn’t get out of bed. David missed work to care for the boys, and chores piled up. Then one day, a neighbor suggested a way to boost her mood and energy: methamphetamine.

“I thought, ‘I’ll do it once and I’ll clean my house,’” she said. “That’s my biggest regret, because that one time turned to two times.”

Related story: Foster care task force gets initial OK from Kansas House

Tara and David still provided for their children and didn’t use drugs in front of them, but their increasingly heated arguments took a toll on their older son’s emotional health. When a family member reported the couple to the Kansas Department for Children and Families, Tara feared caseworkers would remove her kids from their home in order to protect them. But now Tara thinks God used the state’s intervention and services to save her family.

While some caseworkers weren’t sympathetic to their situation, others saw that Tara and David could be good parents if they received mental health treatment, she said.

“The parent is probably somebody who used to be that child [in need of care] and needs to be healed for that child to have a chance,” she said.

Family preservation services — including training for parents, referrals for food assistance and other support — are designed to promote that healing. According to DCF, most families that receive preservation services succeed: About 82 percent of families who participated statewide were able to avoid having a child removed from the home.

But many at-risk families don’t receive preservation services, and some people who have worked for years in the social services system say the lack of help is pushing more children into foster care.

Foster Care Numbers Up Nationally

Kansas privatized its foster care system in 1997. Currently, DCF investigates cases of alleged abuse and neglect, while two private contractors — KVC Health Systems Inc. and Saint Francis Community Services — place children in foster homes and arrange support services. District courts determine whether children should go into foster care and when they should leave it.

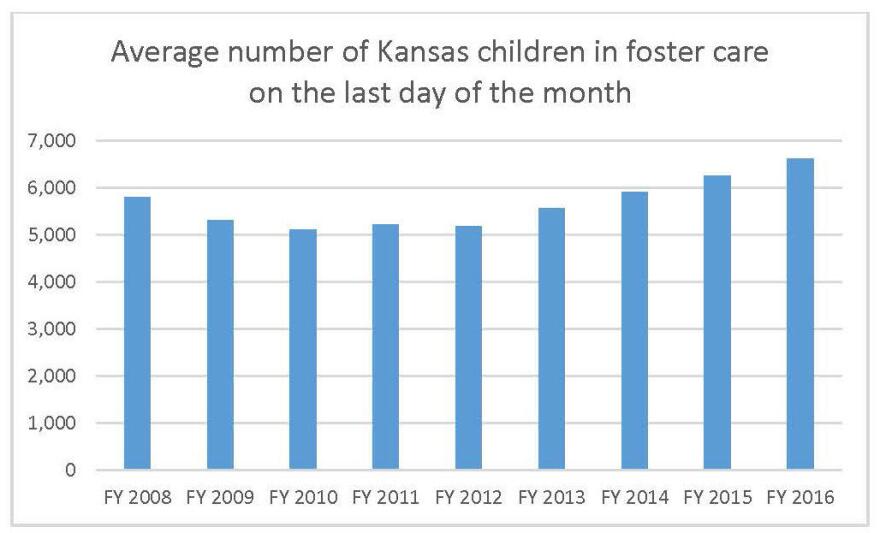

Over the last four years, Kansas has repeatedly set records for the number of children in foster care. More than 7,000 children were in the custody of the state foster care system at the end of March, up 38 percent from the same time in 2012.

The number of children in foster care also has been rising nationwide, said Deneen Dryden, director of prevention and protection services at DCF, which oversees the child welfare system. The Kansas rate had a larger increase, however.

DCF Secretary Phyllis Gilmore said parents’ mental health and substance abuse disorders have contributed to the rise in children in foster care, as did what she describes as a general “breakdown” in families. State agencies are working together to increase access to behavioral health treatment, she said, but that alone won’t help all families.

“It’s not just one thing or we would have figured it out,” she said.

Others familiar with the foster care system, however, say Kansas officials have put more emphasis on finding foster and adoptive homes than on preventing child abuse and keeping children with their birth parents.

For much of the last decade in Kansas, the number of children placed in foster care has gone up when the number of family preservation cases has dropped.

In the 2013 fiscal year, for example, 394 fewer families were referred for preservation services than in 2010 and 530 more children entered the foster care system. The association appears to work both ways, because fewer children entered the system in the 2014 and 2015 fiscal years, when the number of families receiving preservation services increased.

Still, fewer families are receiving preservation services than at the start of the decade and more children are entering foster care.

Dona Booe, CEO of the Kansas Children’s Service League, said state and federal funding for family preservation services and community-based abuse prevention programs eroded over the last decade, particularly since 2011, when Republican Gov. Sam Brownback took office. The Kansas Children’s Service League uses government and private funding for programs designed to prevent child abuse and neglect before the state become involved, while families only receive preservation services after a report to DCF.

Booe said the abuse prevention programs target families that are at risk because of a history of domestic violence, substance abuse or even low educational attainment as early as possible — in some cases, before a child is born.

DCF philosophy also has shifted over the last six years to emphasize serving at-risk children through foster care instead of community-based programs, she said.

“There’s clearly an emphasis in recruiting and finding families to adopt,” she said. “It is really a policy decision about how you’re going to care for [at-risk] children and families.”

Foster and adoptive homes are necessary for the worst cases of abuse and neglect, Booe said, but preventing abuse would reduce the number of children who have to be removed from their homes, allowing caseworkers to put more effort into the most serious cases.

The increase in foster care numbers also coincided with smaller state budgets and less tax revenue after 2012 income tax cuts pushed by Brownback. New limits on cash assistance, child care and food stamp programs designed to help at-risk Kansans also may place families under more stress, social service advocates say.

Wyandotte County Judge Dan Cahill, who spoke to lawmakers earlier this year about his experience with children in need of care cases, said reduced access to family preservation and other services like mental health treatment have pushed more families into the foster care system, he said.

"We have to deal with, ‘We might be able to keep that kid in the home, but we don’t have access to that service,’” he said. “When we take a child from a home, we are going to cause trauma to that child. That has to be weighed against the danger of leaving a child in the home.”

Steady Spending On Preservation

But Dryden of DCF said the state just doesn’t have the funding to offer family preservation services in every case where they might be useful. Federal funds cover only about 37 percent of the cost of family preservation services, she said.

Spending on family preservation services in Kansas has held roughly steady in recent years, fluctuating between $9.7 million and $10.2 million since 2012. At times, however, fewer families have received services as the cost of providing them grew.

During the same period, the state’s spending on foster care increased as more children entered the system. Federal and state spending on foster care in Kansas is expected to total $163 million in the current budget year, up from $135 million in 2012. Budget projections released in April show DCF expects to spend about $181 million on foster care in the budget year starting in July.

DCF has pursued about $1 million in additional funding for family preservation programs next year, including a $500,000 federal grant, Gilmore said.

“We have strong data that shows children do best in their biological home, if they are safe,” she said. “All efforts we can do, we do to keep the home intact.”

The rest of the funding for increased services would have to come from the Kansas Legislature — a challenging prospect with a nearly $900 million budget gap over the next two years.

“All efforts we can do, we do to keep the home intact.”

The foster care budget limits the number of families that can receive assistance, said Steve Edwards, director of family preservation services at Saint Francis Community Services, the contractor for western Kansas. A lack of drug treatment options in western Kansas also is a challenge, he said.

“Having more resources for assessment and treatment, particularly in the more rural counties, would help,” he said.

Jenny Kutz, director of communications for KVC Health Systems, the state contractor for eastern Kansas, said the success rate for families receiving preservation services has been as high as 95 percent in the Kansas City area, where parents have easier access to mental health and substance abuse treatment and support from programs like Head Start.

“More resources toward prevention both in our state and nationally would be great for families,” she said. “It allows more families to be served and it allows child welfare professionals to have more time with the families they serve.”

Past Emphasis On Collaboration

Rochelle Chronister, who from 1995 to 1999 was secretary of DCF’s predecessor, the Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services, said keeping children out of the system was a key part of the reforms that included privatizing foster care services.

“If you reduced the stress in the family, the kids were going to be better off.”

Her department gave its contractors goals, including keeping children in their homes if they would be safe and returning children home or placing them with an adoptive family as quickly as possible, she said.

“Obviously, if families can be kept together, with the children still being safe, that’s the best way to go about it,” she said.

Chronister said she also emphasized that caseworkers collaborate with colleagues in other departments to address a family’s needs, whether they included mental health treatment, job training or child care assistance.

“Things that helped them get out of poverty were also more liable to reduce the stress in their home,” she said. “If you reduced the stress in the family, the kids were going to be better off.”

Tara Fritz, whose family received preservation services three years ago, has seen how those services helped her children.

Their younger son, who was an infant at the time, doesn’t seem to remember his parents’ troubles and hasn’t shown any lasting effects. Their older son still receives therapy, but Tara said she hopes the services have broken the cycle of trauma so that her son’s children won’t have to live through it.

“He can heal now and not heal when he’s 40,” she said.

Meg Wingerter is a reporter for the Kansas News Service, a collaboration of KMUW, Kansas Public Radio and KCUR covering health, education and politics. You can reach her on Twitter @MegWingerter.