An aide for Kansas Governor Sam Brownback says expanding Medicaid to cover more low-income, but able-bodied adults would be “morally reprehensible.” As Jim McLean of the KHI News Service reports, the comments are the latest in a growing war of words over the contentious issue.

Below is the full story from KHI News:

The Medicaid expansion debate in Kansas is heating up.

Big time.

The pending closure of Mercy Hospital in the southeast Kansas community of Independence appears to be the catalyst.

Soon after hospital officials announced plans to close the facility, expansion advocates went on the offensive, charging that the state’s rejection of Medicaid expansion helped seal its fate.

Now, expansion opponents, including Gov. Sam Brownback and Lt. Gov. Jeff Colyer, are firing back.

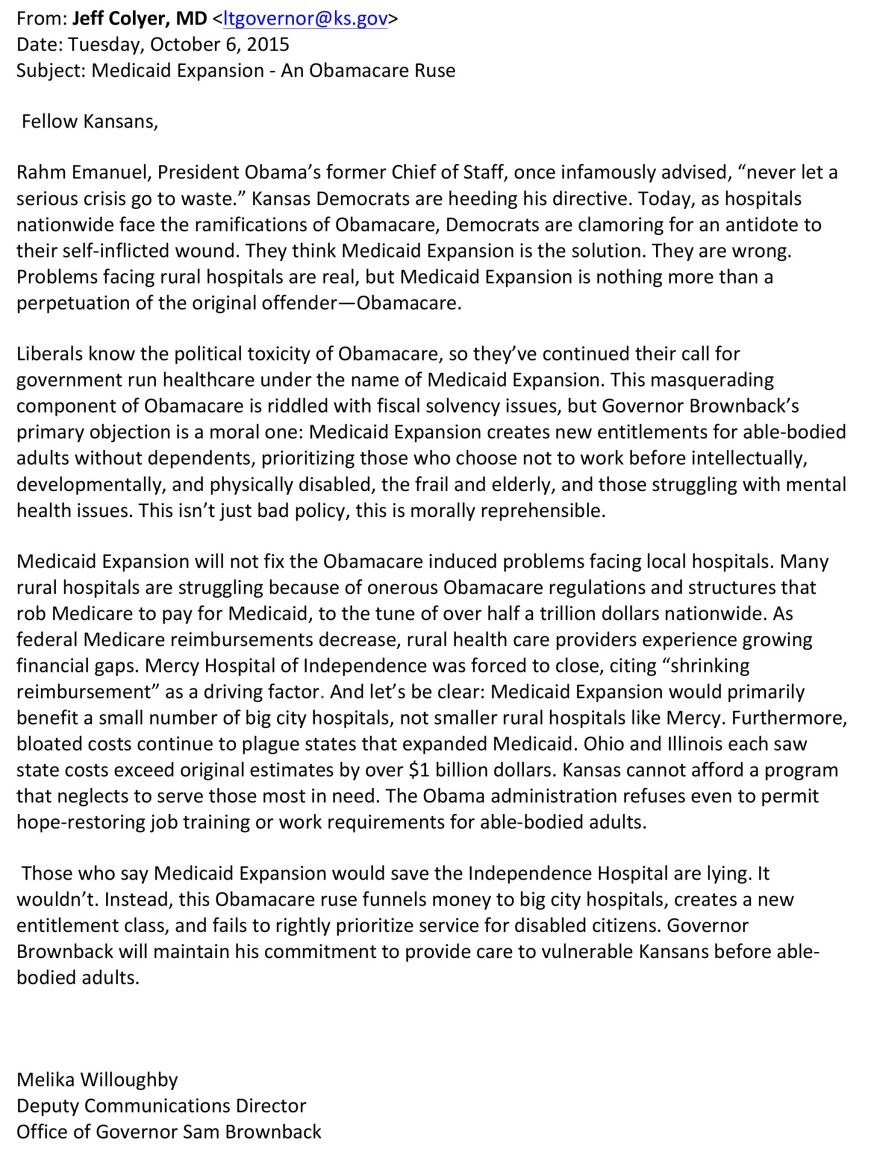

A message sent to Brownback supporters Tuesday by Melika Willoughby, the governor’s deputy communications director, criticizes “Democrats” and “liberals” for using the hospital’s closure to make their case for expanding KanCare, the state’s privatized Medicaid program.

“Medicaid expansion will not fix the Obamacare-induced problems facing local hospitals,” Willoughby wrote in a message forwarded by Colyer.

Colyer, a plastic surgeon who is thought by many to be the administration’s staunchest opponent of expansion, made similar arguments in responding to a recent Salina Journal editorial in favor of Medicaid expansion.

In her message, Willoughby says that reductions in Medicare reimbursements triggered by the Affordable Care Act and exacerbated by automatic budget cuts in 2013 to avert a shutdown of the federal government are the main problem for struggling rural hospitals.

“Let’s be clear: Medicaid expansion would primarily benefit a small number of big city hospitals, not smaller rural hospitals like Mercy,” Willoughby wrote.

Talking points memo

The arguments in the message to Brownback supporters mirror those contained in a memo written for Republican legislative leaders and obtained by the Heartland Health Monitor partner KHI News Service. The GOP talking-points memo says that costs have far exceeded estimates in many states that have expanded their Medicaid programs. It also asserts that the low-income adults who would gain coverage under expansion are capable of taking care of themselves.

“The population Medicaid expansion would cover mostly consists of healthy adults without children, who could receive private coverage if they work 33 hours a week at the minimum wage,” the Republican memo says. The memo is referring to the earnings threshold at which low-income Americans become eligible for federal tax credits to help them purchase private coverage through the online marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act.

Willoughby sharpened the point in her message, writing that Brownback’s primary objection to expansion is a moral one.

She wrote: “Medicaid expansion creates new entitlements for able-bodied adults without dependents, prioritizing those who choose not to work before intellectually, developmentally and physically disabled, the frail and elderly, and those struggling with mental health issues.”

The claim that expansion would put those newly eligible for Medicaid ahead of the disabled drew strong reactions from expansion advocates.

“I think it’s deliberately misrepresenting what sort of services people are getting and what they’re eligible for,” said Sheldon Weisgrau, director of the Health Reform Resource Project, a pro-ACA initiative funded by several health foundations in the state. “We still seem unable to have an honest discussion about this based on facts. We’re still just mired in politics and misinformation, and it’s disappointing.”

For instance, Weisgrau said, most of the low-income adults who would gain coverage work at least part time. In addition, he said, Kansans with physical and developmental disabilities aren’t on waiting lists for health care services and wouldn’t be displaced by expansion.

“The disabled folks are in KanCare and getting medical services,” Weisgrau said. “They’re waiting for the state to make home and community-based services available to them.”

Hospitals respond

A point-by-point response to the GOP memo prepared by the Kansas Hospital Association says that only 18.2 percent of the Kansans who would be covered by expansion are unemployed. It says that 54.4 percent of them have jobs.

“These Kansans work as dishwashers, housekeepers, health care support workers, janitors, nursing assistant, landscapers, bus drivers, child care workers, medical assistants, retail sales people and fast food workers in Kansas communities,” the KHA memo says.

The remainder of those who would gain coverage are either disabled or women with children under the age of 18.

KanCare now covers about 425,000 low-income children and families, plus disabled and low-income elderly adults.

Adults with dependent children are eligible for KanCare coverage only if they have incomes below 33 percent of the federal poverty level, $7,870 annually for a family of four. Non-disabled adults without children aren’t eligible regardless of their income level.

Expansion would extend KanCare coverage to non-disabled, childless adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level: $16,105 annually for an individual and $32,913 for a family of four.

In response to other arguments mounted by opponents, the KHA memo says that the billions of federal dollars that would flow into the state under expansion would more than offset the Medicare reductions for many Kansas hospitals.

“Medicaid expansion is the solution to recouping these lost federal funds,” the memo says, noting that the state’s smallest critical access hospitals would see an average net gain of about $370,000 a year.

Expansion would generate an average of approximately $1.3 million a year for medium-size hospitals and $9.2 million for large providers in Wichita, Topeka, Lawrence and Kansas City, Kan., according to the memo.

A previous KHA analysis said that expansion would provide Kansas hospitals overall with nearly $100 million more per year than they stand to lose due to the reductions in Medicare reimbursements.

In the memo, KHA officials acknowledge that Medicaid expansion costs have exceeded estimates in some states but noted that “not one has decided to repeal” its expansion plan.

“While Medicaid expansion has not always been implemented smoothly, the information provided (by opponents) does not tell the whole story,” the memo states.