On Sept. 4, KMUW aired a story about policing in Sedgwick County. We took a look at military equipment acquired through the federal government's 1033 program, including a newly acquired armored vehicle. The following story also focuses on policing in Wichita.

A public meeting was held last week called “No Ferguson Here.” It was in response to the events in Ferguson, Mo, where 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot and killed by police. City officials in Wichita met with citizens to discuss the relationships between area police and the people they serve.

A common theme weaves through the crowd at Wichita East High School: this is to be a beginning, the beginning of a discussion that needs to be revisited again and again. Those in attendance say they watched the footage of rioting and protesting in Ferguson, Missouri and many fear that the tensions that simmered there for years might also be present in their own communities. Larry Burks is Vice President for Wichita’s NAACP chapter.

“I decided to come out because I'm member of the community, and we're concerned about the issues that have happened in places like Ferguson, and we have a vested interest in our community here. We need to have a dialog, so we can put issues on the table and discuss things, so we can, in fact, air those issues.”

Marvin Stone is seated a few rows back from the stage; he and his wife Patricia await the beginning of the forum.

“I’m still not convinced that a black male walking down the street is not going be accused of doing something. That's why I'm here tonight.”

A group of panelists walk on stage and take their seats. They are Mayor Carl Brewer, Deputy Police Chief Norman Mosley, City Manager Bob Layton, Wichita Branch NAACP President Kenya Cox, Kansas People's Action President Carlos Contreras and Rev. Reuben Eckels of Sunflower Community Action. They would ask questions for more than an hour and a half.

“What we’re committed to doing in the city is to listen to the concerns, possibly offer some solutions, but more importantly, commit that we’re going to work together on those solutions,” Layton tells the crowd. “So, I think the call to action is appropriate and to not just come up to a meeting like this and then disappear.”

A concern echoing through the predominantly African-American crowd is that officers unfairly target and harass black citizens.

In the audience, Marvin Stone continues: “I was a professional investigator for the state. I was pulled over by the police because a robbery or burglary had happened. Burglars don’t wear a three-piece suit and carry a briefcase.”

Rev. Reuben Eckels of Sunflower Community Action says a public advisory board with subpoena power should be established to review racial profiling complaints filed against the city.

“It would give us accountability. It would begin to change the perception that people are shut out of the process.”

Carlos Contreras, president of Kansas People’s Action, says he’d like to see more of an effort by the Wichita Police Department to understand the communities that they serve.

“We need a little more cultural sensitivity training, especially when you have differences in language, differences in backgrounds. When you have a high immigrant population, you tend to have people that come from countries where there's high corruption in government, so they already have a high mistrust in the authorities that be.”

The crowd also asked that body cameras be worn by all police officers, but ongoing discussions between the city and its police union may determine whether officers can actually be forced to wear body cameras.

The Takeaway

On the fourth floor of Wichita’s City Hall, Deputy Police Chief, Nelson Mosley sits with pages of notes he jotted down during the “No Ferguson Here” meeting. He says he hears the calls for accountability. He is concerned that some citizens fear his police force.

“I don't like hearing that. We have an open door policy. If there's something that any community member needs to tell us, please reach out and tell us. That’s our objective—heck, it's in our mission statement: to police in a fair and ethical manner.”

According to the Kansas Attorney General’s Office, over the past three years there have been 58 racial profiling complaints filed against the Wichita Police Department. None of them have been substantiated. Deputy Chief Mosley says that they look at these cases as if they’re any other investigation.

When asked if he believes he has racially biased police officers on his force, Mosley says that he can’t know the motives of his police officers.

“It’s like me asking you - your motive. How would I know? I can ask you that but, at the end of the day, do I really know? I have to go by what you tell me.”

Mosley is officially named Interim Police Chief on September 6th, 2014, when Norman Williams retires after 14 years at the helm.

“We’re transitioning right now. There's a search out soon for a new Police Chief. On top of that, we're doing analysis of this department, looking at what are we’re doing right, what are we’re doing wrong, what we could be doing better. We're looking at everything. What I'm asking is that we are allowed time. All of these things won't happen overnight.”

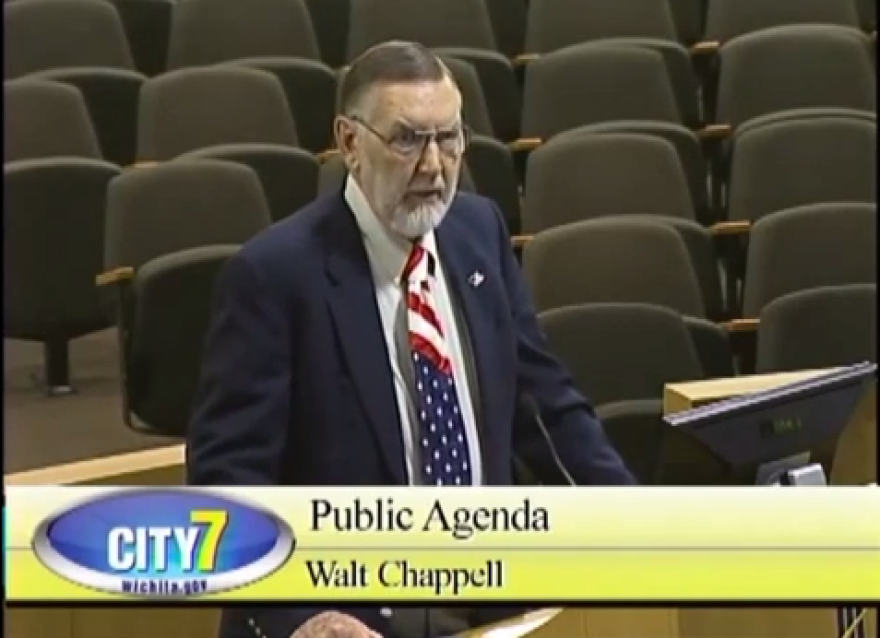

If you ask some community leaders, the Wichita Police Department has had plenty of time to address public concerns. Walt Chappell serves on Wichita’s Racial Profiling Advisory Board, which drafted a statute passed by the Kansas Legislature in 2005. It formed racial profiling agencies throughout the state. Chappell says the law has since been watered-down and advisory boards hold little, to no, power.

“The police chief has not come to our advisory board. He sends delegates, people he's appointed. We ask questions—we very seldom get any answers. If they're not looking for profiling, then they're not going to find it. If they're not checking on the excessive use of force that their officers are doing on the streets, they're not going to find it.”

For proof of racial profiling, Chappell cites a recent study by Wichita State University, which indicates that, in 2013, black motorists were pulled over and ticketed at twice the rate of white motorists. Previous studies in 2001 and 2004 indicate that the disparities aren’t narrowing, but getting worse. Chappell says that the “No Ferguson Here” meeting, while belated, was an important first step.

“This was something we've been asking for the city council, city manager and the mayor to be involved with for years. Over 600 people showed up. It was standing room only. It was amazing to see how many folks spoke up and said, ‘My God, this has got to stop.’”

Chappell would also like to see advisory boards hold subpoena power, something only seen in a handful of cities.

Chappell disagrees, however, that body cameras for officers are a solution. He believes it wouldn’t affect unwarranted stops, and fears videos wouldn’t be accessible to the public.

A Look Forward

Pastor Kevass Harding unlocks the door to Dellrose United Methodist Church. He flicks the lights on and sits down in one of the pews his congregation fills every Sunday. He helped organize the “No Ferguson Here” meeting. He says that after seeing the Ferguson footage of riots and protests over Michael Brown’s death, he thought a discussion needed to take place in Wichita.

He was a Wichita Police Officer for five years. He had aspirations of joining the FBI but says he found a higher calling in the clergy. He has no doubt that racial profiling is a problem for Wichita’s minority populations, having experienced it himself.

He begins a story about his rookie year on the force; driving to work in his Honda, which had densely tinted windows and 22-inch rims, he missed his turn and ended up in a “white neighborhood.” A police officer pulled him over. Due to his tinted windows, the police officer could not see who he had pulled over.

“I rolled the window down and he was immediately like, ‘oh my god,’” Pastor Harding says. “I say, how you doing? I say, why did you stop me? And I could see him searching for a reason. I wouldn't even say he was racist, it's just that he thought, here's a person I don't think should be in this neighborhood.”

Pastor Harding says that while his time with the police force was positive, racial profiling still exists; he hears concerns from his own congregation.

“There’s a bigger systemic issue here,” he says. “It’s not just the police, but poverty, education, jobs. Hopefully, we can develop [No Ferguson Here] to be larger than just police and community relations.”

Harding says the problems he sees between minorities and the City of Wichita can be helped through the dialog that was started last Thursday. But he says it can’t afford to lose momentum.

Follow Sean Sandefur on Twitter, @SeanSandefur

Originally aired on Morning Edition on 09/05/14