A collection of documentary photographs from 1974 is currently on display at the Wichita Art Museum. Black and white images of farmers, haystacks and shop fronts provide a look at rural Kansas as seen through the lens of three photographers. KMUW’s Sean Sandefur visited the gallery with one of those artists and has this report.

Inside the Wichita Art Museum, looking at work he created 40 years ago, is a man with deep roots in Kansas.

Larry Schwarm teaches photography in the School of Art and Design and Creative Industries at Wichita State University. He grew up in Greensburg, Kansas and studied photography at the University of Kansas.

He stands before gallery walls lined with dozens of black and white photographs taken by himself and two other artists in the summer of 1974. The exhibition is called ‘No Mountains in the Way,’ and was the idea of a fellow photographer.

“This was a project organized by a man named James Enyeart. He was at the University of Kansas Art Museum," Schwarm says. "He came up with an idea to photograph the state of Kansas along the lines of what was done during the Great Depression, with the photographers of the FSA.”

The Farm Security Administration, or FSA, was part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal campaign. It sought to address rural poverty during the Great Depression. In order to show Congress the plight of families in places like Oklahoma and Texas, the federal government paid dozens of photographers to travel across the U.S. from 1935 to 1944.

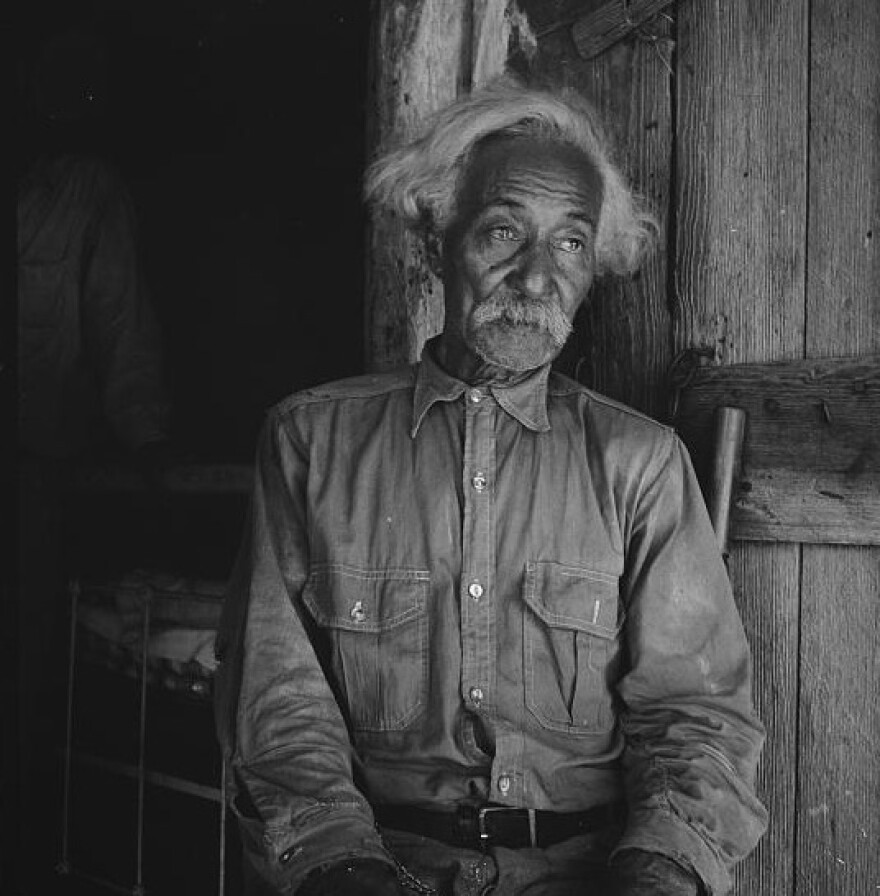

The work of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein and others showed the weathered faces of farmers and their empty fields, the despair and anxiety of mothers and their children.

But they also showed resilience.

Much like the government-funded artwork of the FSA, Larry Schwarm, Terry Evans and James Enyeart—all of whom lived in Kansas in 1974—used a National Endowment for the Arts grant to document the rural corners of the Sunflower State.

“It was very loosely organized," Schwarm says. "Enyeart gave us a lot of latitude. He said that he was going to photograph small-town, vernacular architecture. Terry Evans was going to focus primarily on the people of Kansas and I was to do the landscape of Kansas.”

Schwarm wasn’t exactly thrilled at being assigned to document the landscape of Kansas. He was much more interested in documenting people. But Enyeart had a feeling Schwarm would produce intriguing work with agriculture as his backdrop.

“I think what he saw, which I didn’t realize at the time, was that having grown up on a farm, having always had my fingers in the dirt, I understood what crops were about, I knew how to talk to farmers," he says. "I had an appreciation for the land that can only happen when you’re that intimate with it. So I was able to photograph a very subtle landscape and dig out of that things that were interesting.”

Many of his photographs are square—about the size of a greeting card, matted in white cardboard with silver frames.

Rural life—with its haystacks, barns and tractors—might not seem captivating. But dramatic lighting and the use of patterns, shapes and varying tones, transform their banality.

Two of Schwarm's compositions depict grain elevators, photographed close to their base, looking up at the tall structures. A vibrant blue sky is represented in dark gray. Schwarm says he’s always been attracted to these monoliths. To him, they’re the landmarks of western Kansas. He likens them to the cathedrals of France.

“About every ten miles [in Kansas], there’s another small town. And every town has a grain elevator. When you’re in Greensburg, Kansas, where I grew up, you can look in one direction to Haviland, Kansas, and you can see the grain elevators. You look the other direction, it’s 10 miles to Mullinville, Kansas, and you can see the grain elevators. So, they’re almost like stepping stones," he says.

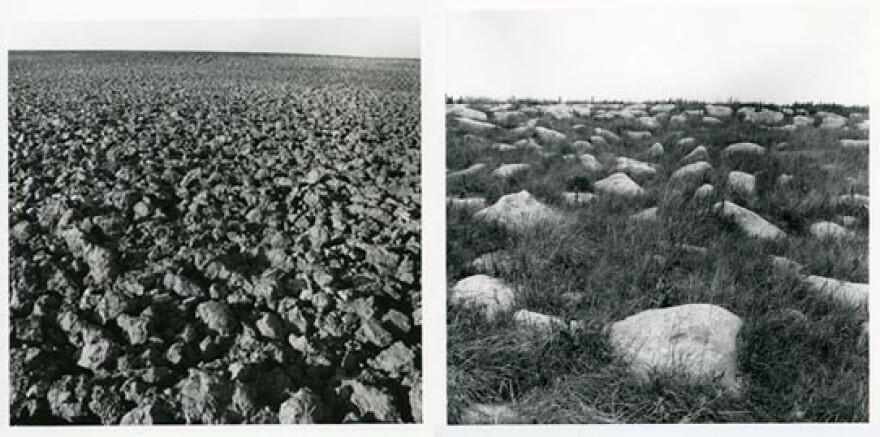

Whereas the two photographs of grain elevators force you to look to the sky, another series of photographs focuses on the earth. The first is unmistakable: Large rocks in the Flint Hills jut out from the grass. The horizon only takes up a small section at the top of the composition. For Schwarm, these rocks represent the impossibility of ever farming here. Juxtaposed against this idea are three photographs of tilled soil, taken in Clay County, Kansas.

“Someone pointed out to me that of all the photographs up here, mine are probably the least historical. [In Enyeart's and Evans's photographs], styles have now changed, a lot the buildings have been torn down and new ones have been built," Schwarm says. "But [my photographs are historical] in a lot of ways, because these methods of farming are no longer used. You would never moldboard plow like this anymore."

Schwarm says he enjoyed documenting the Flint Hills. The photograph he is most proud of from this series sits off by itself in the exhibition, and represents a starting point for his journey across Kansas.

It’s a wide shot of the Flint Hills, seen through a derelict gate. Two large, wooden posts are barely holding together a metal fence.

“It was an area that I had driven through numerous times, but really didn’t know too well until this project," Schwarm says. "The whole idea is a gate being a device where it takes you, the viewer, from one place in to another place, just the same as it does in real life. And there’s this tension of the post there. They look like they’re both pulling apart and leaning in at the same time. And it just framed that vast landscape in a way that I had never really looked at before.”

Larry Schwarm has used this series as a springboard for the rest of his award-winning career. Since ‘Not Mountains in the Way,’ he has gone on to closely document the controlled fires of the Kansas plains and the faces and settings of Kansas farms.

He takes a step back to survey the work of Terry Evans, James Enyeart and himself—work that is now archived at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Schwarm, like the subjects and settings of his photographs, is forever linked to those hot, summer months in 1974.

“To have work at an art museum that you did when you were really young, I’d like to think I’ve gotten a lot better. But, when I walked in, I was actually quite proud of them," he says.

The photo series ‘No Mountains in the Way’ can be viewed in the Paul Ross Gallery and Scott and Carol Ritchie Gallery at the Wichita Art Museum until Jan. 3.

"No Mountains in the Way, 40 Years Later: Kansas Documentary Photography" is on display courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery

--

Follow Sean Sandefur on Twitter @SeanSandefur.

To contact KMUW News or to send in a news tip, reach us at news@kmuw.org.