Almost one-third of the food produced in America goes to waste.

Using the motto, "Feed people, not landfills," the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Agriculture are working with partners across the country to change that. Their goal is to reduce food waste by half over the next 15 years.

Heartland Health Monitor’s Bryan Thompson recently traveled to Wichita to see how a Kansas grocery store chain is working with community organizations to help meet that goal.

A refrigerated truck backs into the loading area behind a Dillon’s store in west Wichita. The driver, David Allen, opens the cargo door, pulls out a folded metal cart, and enters the stockroom through a roll-up door.

The first stop is a huge walk-in freezer. Some days, it contains meat for him to pick up--but not today. There is, however, a good haul from the bakery department.

Today, it’s 14 large boxes of bakery products. They’ve been removed from the shelves because they no longer meet Dillon’s standards for freshness. But that’s no reason to waste them, says Misty Cavanaugh. She helps Dillon’s stores match supply to demand.

“The bread that we produce here in our bakery, we actually pull that the day that it expires," she says.

The bread and baked goods from this store will end up at the Kansas Food Bank in downtown Wichita. From there it will be distributed to food pantries, soup kitchens and shelters.

“Year to date, our division as a whole, which is 82 stores, we’ve actually donated 820,000 pounds of food," says Jeremy Maples, who oversees the food donation program for Dillon's stores.

Maples says that’s the equivalent of more than 600,000 meals—and that’s just through the first nine months of the year. All of this food used to end up in landfills. Kansas Food Bank director Brian Walker says now it makes up a large and growing portion of the food service organizations use to feed hungry people in 85 counties.

“I would say it’s probably a third. It’s millions of pounds a year," he says.

Walker says food recovered from grocery stores is increasingly important, because shelf-stable products from manufacturers have gotten harder to come by over the last few years. On this day, food bank trucks picked up almost a ton of food, including 1100 pounds of baked goods, and 700 pounds of meat.

“There are lots of rules that go along with this," Walker says. "You know, we have to make sure the product stays safe, that it stays frozen, so it remains a good product.”

Walker says much of the food recovered from supermarkets is more nutritious than shelf-stable products like microwave popcorn or boxed macaroni and cheese—but not all of it. The baked goods include donuts, cakes and pies. Walker says his agency is the Food Bank, not the food police.

“If that food can feed somebody, why not put it in their belly? If that food makes a child happy, you know, why don’t we put it to good use? Why do we want it to go to the landfill, when somebody can still eat it, you know, even a birthday cake? Why shouldn’t a child have a birthday cake?” he asks.

The food recovery program has existed in some form for years, but it really ramped up in 2013 and 2014, thanks in part to research from two interns with Kansas State University’s Pollution Prevention Initiative. That’s right, the Pollution Prevention Initiative. Turns out, there is a direct connection between decomposing food and pollution, says Nancy Larson, director of the research initiative.

“When it goes to the landfill, we know that it creates methane gas, which is actually a very potent greenhouse gas," Larson says.

Twenty-five times more potent than carbon dioxide, to be exact--add to that all of the water used to grow the food, and all of the fuel used to produce, process, and ship it. “This is what drives me crazy," Larson says.

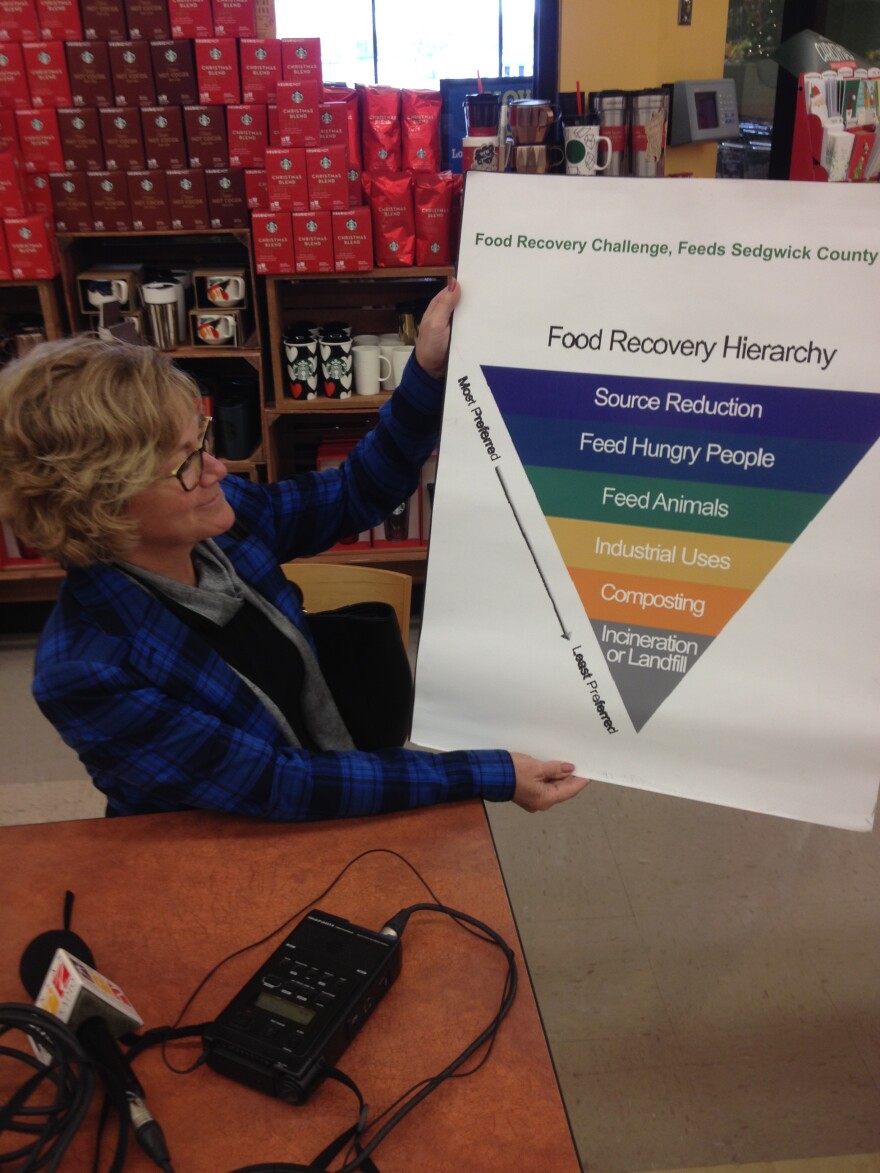

Which explains why Larson is on a mission—one that dovetails nicely with Walker's mission at the Kansas Food Bank. Larson says the best way to keep food out of the landfill is to reduce excess production, and to get better at using potential waste to feed people and animals--or even as compost for crops.

As Larson sees it, taking unused food to the landfill should be the very last resort.